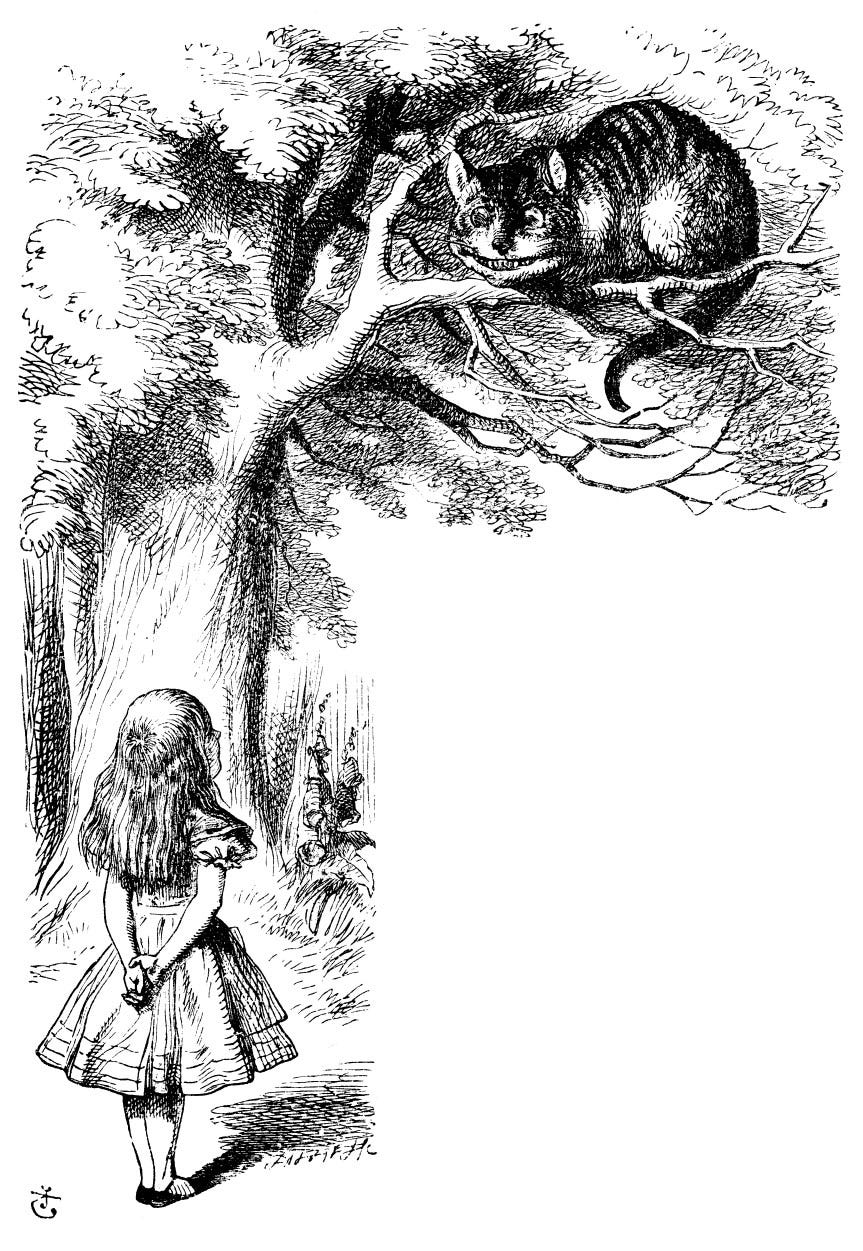

Escaping Wonderland

A journey through madness, illusion, and awakening.

“But I don’t want to go among mad people.”

“Oh, you can’t help that — we’re all mad here.”

Falling down the rabbit hole, I reached out to save myself, always catching some absurd construction labelled Sweet Marmalade. The promise of something sweet was enticing, yet always was there a bitter aftertaste. Each time I hoped for comfort, I found only dissatisfaction.

Madness, I have discovered, is truly like Wonderland: both deadly and serene. My own descent into it began when I was about Alice’s age — innocent, self-contained, and curious enough to believe that sense could be made from nonsense. The fall down that rabbit hole was inevitable. I was surrounded by mad people and there was no escaping the logic of their world. As the Cheshire Cat tells poor Alice, he is mad and so is she. Resistance, then, is quite futile.

Recently, I managed to claw my way out of that hole. Unfortunately, it wasn’t as simple as growing tall and waking up. I had to retrace my steps, unlearn every distorted lesson, and submit myself to the book with no pictures; the unadorned truth of life. I had to surrender the fairytales that once protected me and discover that the real magic of the world is not imagined, but seen with clear eyes.

Being trapped in a world of madness is terrifying. Like Alice, who must define herself to a smoking Caterpillar before he’ll even speak to her, I found myself in a place where nothing stayed upright, nothing stayed true, and even language itself seemed to sneer.

“You! Who are you?”, the Caterpillar demanded.

Growing up, we’re told we must know who we are. We’re given forms to fill, roles to play, and boxes to tick: a mind-map of the self drawn before we’ve even learned to breathe. Why should we have to explain ourselves at all? Why can’t we simply be?

Holding ourselves together by mental force could be the first sign of madness. Alice tells the Caterpillar she cannot explain herself because she’s changed so much that day — which, of course, is true of everyone. We change with each hour and each encounter. Morning might find me wishing to hibernate like a bear; by afternoon I’m a Disney princess singing to the birds; by evening, a sultry vixen coaxing my partner into erotic dance. Who, then, is the “real” self?

As little Alice wanders through Wonderland, she keeps trying to prove she knows the rules. She recites what she’s been taught only to find the words betray her.

“How doth the little crocodile improve his shining tail, and pour the waters of the Nile on every golden scale…”

The moral poem she means to recall has turned carnivorous. Virtue has become appetite and language seems to preference chaos to order.

Perhaps madness begins there, in the demand to remain coherent while the world keeps rearranging itself.

Lewis Carroll framed Alice’s adventures as a dream and many have read them as a playful metaphor for altered states or psychedelic revelation. To me, however, the dream was the only part of the story that ever felt real.

The world outside — the lessons from her sister, the polite idleness by the fireplace — has always struck me as the illusion. Wonderland, for all its nonsense, tells the truth: that society is absurd, adults are unreliable narrators, and logic can be as cruel as chaos.

For most of my life, I too lived among mad people in one form or another, trying to fit their contradictions into some workable map of sense. Like Alice, I kept believing I could reason my way through, if only I learned the right words.

My childhood was also spent observing, decoding, and forever analysing the behaviour of others while longing for simplicity. Eventually, I realised that the real dream was not Wonderland at all, but the so-called ordinary world we mistake for sanity.

With nonsense expectations and obligations thrown at me from family, society, and culture, coming of age was a perilous game. One where the rules kept changing and no one would admit it. I was asked to internalise what I didn’t understand, to trust that it would all make sense someday. It never did.

I grew up between Ireland and Africa. Two wounded worlds shaped by their own histories of violence. In both places, the adults moved through pain they couldn’t name, surviving on rituals of avoidance that looked, to a child’s eyes, like normal life.

In Africa, I ran wild with friends through the bush, the world vast and unsupervised; then suddenly I was in Dublin, where the air was thick with smoke and music, as stoner parties were hosted in our narrow terraced house. It was another Wonderland entirely but the same madness dressed in a different costume.

I watched and tried to make sense of what I was seeing, believing that if I observed closely enough, I might find a pattern that explained it all. In hindsight, I was witnessing cultural madness. A kind of collective dream where everyone had agreed not to wake up.

The older I grew, the more I retreated into my own world. It felt safer there.

In Through the Looking Glass, Alice enters the Wood Where Things Have No Names. She forgets herself completely. This is not amnesia but a brief return to consciousness without identity. There she meets a fawn who has also forgotten itself. The two walk together through the trees, Alice’s arms wrapped lovingly around the creature’s neck. For a moment, neither knows what or who they are, only that they are together, alive, and unafraid.

When they emerge from the wood, the fawn suddenly remembers: it is a fawn, and she is a human child. The cultural script returns. Fawns are afraid of human children. The fawn darts away, and Alice is left alone again.

There are few moments of peace or safety in Alice’s adventures, but that one has always stayed with me. When I walked in forests as a child, I too would forget myself, I still do to this day. In those green worlds, I ceased to be me and became nobody, or perhaps everybody. I built entire realms where I could live unobserved, unevaluated, and unmade by the madness of others. In those imaginary lands, I could breathe.

It was a form of grace, though I didn’t know it then: the relief of being nameless.

As time trudged along, the madness of Wonderland began to seep back in. The forest grew thin and the trees gave way to mirrors.

To survive I adapted. I mimicked the logic of those around me, speaking their contradictions as if they were sense. I built small systems of meaning to protect myself from the larger absurdities, defining and redefining things until I could no longer tell which definitions were mine. I negotiated reality rather than abiding in it and eventually I myself became an agent of Wonderland.

That was the beginning of my own madness. Not the wild, ecstatic kind that frees, but the orderly sort that imprisons; the madness of accommodation.

Like Alice at the endless Tea Party, I kept changing places, hoping one seat might finally feel right. But the table only grew longer, the cups never emptied, and the conversation circled without end.

But madness was never what I wanted. I only wanted to be safe; like everyone, I suppose. Yet safety, in Wonderland, is just another illusion. The tea is perpetual, the clocks are broken, and everyone insists that this is normal.

Trying to belong looked like learning to smile at absurdities, agreeing with contradictions, and laughing when nothing was funny. The truth was, I wasn’t safe — because I was among mad people, and I was required to pretend that their madness was sanity.

Internalising their logic, I began to live inside a surreal whirlwind of perceptual and linguistic enforcement, contorting my sense of self into something that looked acceptable. I built a persona close enough to my soul’s expression to feel familiar, yet packaged tightly enough to conform to the demands of the Caucus Race. It was not me but I convinced myself that it was.

Eventually, I crowned my own Queen of Hearts. She lived inside my skull and dictated everything to specification. The white roses will be painted red, and any dissent would be met with the same decree:

“Off with their heads!”

Like poor Alice, I stood trial every single moment. My thoughts were witnesses, my emotions the accused. The verdict was always the same: guilty of imperfection.

The madness I suffered was an endless simulation; a theatre of mirrors where every thought reflected another’s distortion. I was never at rest. Everything I said, did, or felt was measured against invisible rules I had never agreed to but somehow obeyed.

My biggest problem was that I lived between worlds. I could not become a true citizen of Wonderland yet I could not escape it either. I was trapped in the borderlands: too lucid for delusion but too conditioned for freedom.

I kept falling down that rabbit hole. Each attempt to orient myself only deepened the descent. The jars of Sweet Marmalade were gone; illusion had stopped offering comfort. The tumbling became perpetual — a maelstrom of madness demanding delusional feed.

I had failed at Wonderland. Failed at believing the lie could ever make sense.

And so at last, I stopped trying and relaxed into the fall. The silence that followed was unbearable at first and vast. In that stillness I started to understand something.

Sanity, I realised, is not the absence of madness, but the willingness to see clearly without demanding that the world make sense.

I reached the bottom of the rabbit hole. Here is where he found me.

“I don’t want to go among mad people,” I whispered.

“Neither do I,” he replied.

He took me by the hand, and as we gazed into each other’s eyes we both felt a presence, a stillness beyond thought, infinite in love and grace. The maelstrom quieted. We just were. Together. At peace. In love.

In that presence, I could see that love can only be embodied, not performed. Then I recognised it, the book with no pictures: the plain, unembellished truth of life itself, without fantasy, fairytale, or painted roses. Only the living page of reality turning before us.

The tumbling ceased. The story was still being written, but not by us. Finally, I was out of the rabbit hole and in the safety of being.

Elsewhere in The Province of the Mind:

Fire Returned to Heaven

This is the introduction to my ongoing series Fire Returned to Heaven: Transcripts from solitary prayer walks recorded over the past years. Each walk was spoken aloud, later transcribed and gently edited for clarity and privacy.